6: Luther’s 95 Theses (October – December 1517)

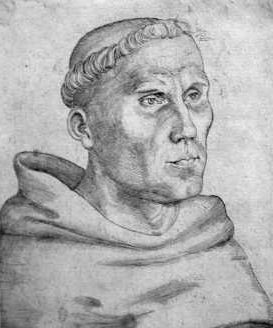

Luther is often pictured as an angry young man, striding through town to forcefully hammer his writings on the Wittenburg church door, to denounce the pope and indulgences so he could start a revolution against the Roman Catholic Church. Nothing could be further from the truth. Picturing Luther as a thoughtful, pious young monk, who was posting questions on the church door (the town bulletin board) in Latin (which most could not read) asking other scholars (not the public) to come or write to discuss not only indulgences, but also church issues such as penance, contrition, confession, and true repentance. He was very concerned over the souls of his flock who believed that with their letter of indulgence, they didn’t have to even go to confession anymore since they had a ticket to heaven. Basically, he was a man concerned with the salvation of his soul and that of others as well, unsure if one could know if he repented enough, and if the pope could really intercede and bestow God’s grace on the dead and release them from purgatory. He had too many questions and doubts and not enough answers. He hoped that discussion with other scholars might help him see things more clearly and help him discover truth. This was the point of disputations at that time. He firmly believed that the church held the keys to salvation, and that the pope was to be obeyed as Christ’s representative on earth. Reforming the church? Not even a thought.

Luther is often pictured as an angry young man, striding through town to forcefully hammer his writings on the Wittenburg church door, to denounce the pope and indulgences so he could start a revolution against the Roman Catholic Church. Nothing could be further from the truth. Picturing Luther as a thoughtful, pious young monk, who was posting questions on the church door (the town bulletin board) in Latin (which most could not read) asking other scholars (not the public) to come or write to discuss not only indulgences, but also church issues such as penance, contrition, confession, and true repentance. He was very concerned over the souls of his flock who believed that with their letter of indulgence, they didn’t have to even go to confession anymore since they had a ticket to heaven. Basically, he was a man concerned with the salvation of his soul and that of others as well, unsure if one could know if he repented enough, and if the pope could really intercede and bestow God’s grace on the dead and release them from purgatory. He had too many questions and doubts and not enough answers. He hoped that discussion with other scholars might help him see things more clearly and help him discover truth. This was the point of disputations at that time. He firmly believed that the church held the keys to salvation, and that the pope was to be obeyed as Christ’s representative on earth. Reforming the church? Not even a thought.

Before writing the 95 theses, Luther had preached and written on abuses of indulgences, and was concerned that indulgences were sold to release souls from purgatory, but requiring no true repentance and contrition. Luther felt that one needed to acknowledge his sinfulness, be disgusted with himself, and turn to a life of constant repentance, seeking God’s grace continuously. An indulgence was only valid after true contrition, but since perfect contrition supposedly already removed punishment, why would an indulgence be needed? And an indulgence was only valid for an actual sin, but what about man’s natural disposition toward sin – original sin? These are the kinds of questions found in the theses.

First of all, although we celebrate the posting of the theses as October 31, 1517, they really were posted in mid November. However, we can still celebrate the Reformation on the 31st, as this is when Luther sent a letter to Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz. The tone of the letter was that of a devout son, full of humility toward a prince of the church, and (pretending?) that he felt sure Albrecht didn’t know what was being done in his territory and in his name. He tells him indulgences are being sold that supposedly redeemed one from every sin, even if he had “raped the Mother of God.” Not only was the sin forgiven, but also the guilt. He tells Albrecht that he (Luther) knows nothing about the certainty of salvation, but surely piety and good works are better than indulgences, and he reminds Albrecht that Christ never preached indulgences. Luther tells Albrecht he is afraid that if he doesn’t stop the indulgence trade, someone may come along later and bring shame to him for it. He closes his letter with a plea that he is only doing his duty as one called to be a doctor of theology, and he attaches his 95 Theses. No word is said against the pope or the scholastics supporting indulgences. Luther also sent letters to other bishops at this same time: The result of which was a total of zero response.

First of all, although we celebrate the posting of the theses as October 31, 1517, they really were posted in mid November. However, we can still celebrate the Reformation on the 31st, as this is when Luther sent a letter to Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz. The tone of the letter was that of a devout son, full of humility toward a prince of the church, and (pretending?) that he felt sure Albrecht didn’t know what was being done in his territory and in his name. He tells him indulgences are being sold that supposedly redeemed one from every sin, even if he had “raped the Mother of God.” Not only was the sin forgiven, but also the guilt. He tells Albrecht that he (Luther) knows nothing about the certainty of salvation, but surely piety and good works are better than indulgences, and he reminds Albrecht that Christ never preached indulgences. Luther tells Albrecht he is afraid that if he doesn’t stop the indulgence trade, someone may come along later and bring shame to him for it. He closes his letter with a plea that he is only doing his duty as one called to be a doctor of theology, and he attaches his 95 Theses. No word is said against the pope or the scholastics supporting indulgences. Luther also sent letters to other bishops at this same time: The result of which was a total of zero response.

As to the indulgences themselves, I will give my brief summary of some of the points.

- 1 – 4: When Jesus says “Repent,” he means for the rest of your life. It has nothing to do with the sacrament of Penance. One must hate [the sin in?] oneself, and “mortify the flesh.”

- 5 – 8. The pope can’t remit any sin penalty except those imposed by him or the canons, can’t remit guilt unless he proves God does, for God alone remits sin and guilt. This only applies to living persons.

- 9 – 16: Priests are wicked if they inflict punishment of purgatory on the dying, penalty for sin should be imposed before absolution, the dying are freed from any earthly penalties, and the dying are frightened enough without the church adding to it. Further, the church has no authority in purgatory.

- 17 – 24: It might well be that those in purgatory can gain merit, increase in love, and decrease in fear. If indulgences could free anyone from punishment, it would only be the perfect few, not the masses being sold indulgences. If the pope grants an indulgence it could only cover what he imposed in the first place. Any bishop or curate has as much power over purgatory as the pope.

- 26 – 37: If the pope could release souls from purgatory it would be through intercession, not in the power of the “keys” which he doesn’t have anyway. When money clinks in indulgence seller’s chests, a soul doesn’t fly to heaven, only greed and avarice increase. No one knows whether souls in purgatory want to be redeemed, for only legends back up this theory. Those with indulgence letters will be damned to hell along with the sellers, and one should guard against those who say the pope’s pardon reconciles man to God. No one can be sure he has been contrite enough to earn salvation. Man has constructed the penalties of sacramental satisfaction, and those who teach that contrition is not necessary, preach unchristian doctrine. Any Christian, living or dead, participates in the church and Christ’s blessings.

- 38 – 50: Still in all, the pope’s blessings aren’t to be disregarded as they can proclaim divine remission. More is said about the importance of sincere contrition, and that a Christian seeks and loves to pay the penalties for his sins. Good works of mercy and giving money to the poor are even better than indulgences, as the pope indicates. Love grows from love and makes one a better person. The pope desires devout prayer over the purchase of indulgences, and if the pope knew what the indulgence preachers were doing, “he would rather that the basilica of St. Peter were burned to ashes then built up with the skin, flesh, and bones of his sheep.”

- 51 – 59: Christians should be taught that the pope would rather give his own money, even sell St. Peter, to many who have been sold indulgences. Trust in indulgence letters is useless, even if the pope offered his soul as security. Those who preach indulgences rather than God’s word, or who don’t at least give both equal time, are enemies of Christ and the pope. If indulgences are celebrated with one bell, procession and ceremony, then the Word of God should be celebrated with 100 of each. When the pope distributes indulgences from the “treasures of the church” people don’t really understand what this means. They can’t be merits of Christ and the saints, for even without the pope they work grace for the inner man, and hell for the outer man. St. Laurence said the poor are the treasures of the church. The gospel is the treasure of the church and fishes for men.

- 60 – 81: (This section gets tricky and seems contradictory to other parts.) The keys of the church are the treasure, as the pope has the power of remission of penalties over things he has reserved for himself. The treasure is odious as is makes the first to be the last. Indulgences are acceptable for they make the last to be first, they fish for the wealth of men, but they are the most insignificant of graces. More is said about indulgences being somewhat good, although limited, and should be accepted as such and cannot do away with guilt. To say that the papal coat of arms set up by indulgence sellers is equal to the cross of Christ is blasphemy, and anyone who allows this talk will answer for it.

- 82 – 91: Here begins a list of questions which Luther calls trivial, such as: Why doesn’t the pope empty purgatory for love, instead of building St. Peter’s for money? What kind of piety lets a bad person buy his way out of purgatory for money, but does not let a good person out of purgatory for love? Why doesn’t the rich pope pay for St. Peter’s himself, instead of making the poor pay for it? What greater blessing could come to the church if the pope bestowed blessings and remissions on everyone a hundred times a day, as he now does once a day? Luther then asks that such questions not be raised (although he has raised them!) as it ridicules the pope in front of his enemies. He closes this section by saying indulgences should be preached according to the intention of the pope and doubts would evaporate. Luther closes the theses writing that we should do away with prophets who say “Peace, peace,” when there is no peace, and bless the prophets who say, “Cross, cross.” Christians should follow Christ through penalties, death and hell, and be sure of getting to heaven through trials rather than through the false security of peace.

For a little while nothing happened except several people told Luther he should be careful. Luther told his friends Spalatin and Karlstad that he now thinks indulgences are a deception of souls. His theses were printed in Nuremberg, Leipzig and Basel in December 1517, then translated into German and sent everywhere, thanks to the invention of the printing press. After a delay, Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz got Luther’s letter the end of November, and sent a copy to Rome. And the rest is Reformation history.