1: Germany before the Reformation

1: Germany before the Reformation

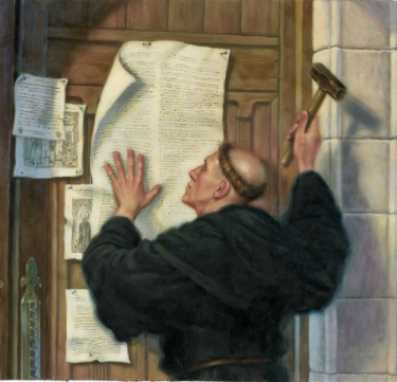

The beginning of the Reformation is generally dated October 31, 1517, when Martin Luther posted his 95 theses on the church door in Wittenberg, Germany. While it is most certainly true he was the match lighting the fuse of the reformation, Europe, and especially Germany, was dynamite just waiting for that match. Although there had been attempts at church reform earlier, notably by Wycliffe in England and Jan Hus in Bohemia, the Catholic Church had suppressed them quickly – generally by burning “heretics” at the stake. Wycliffe got off easily – he was excommunicated 30 years after his death and I doubt that he cared. On the other hand, Jan Hus was burned at the stake. A similar fate was intended for Luther, but happily he escaped, and the rest is history. Luther never wanted a reformation that would split the church – rather he hoped for discussion and correction of what he saw as failings in the church. When Luther posted his theses Germany was ready to explode, and when he struck the match, the explosion was such that the world would never be the same again. The following are some of the factors which had pushed the German people to the brink.

There was strife between the Catholic Church (hereafter referred to as “the church”) authority and civil authority. In essence, the church was the authority on almost everything, and by the end of the Middle Ages, the secular authorities wanted more power and control over their own civil matters. Along with church authority, came several other things which rankled the people. The church was exempt from taxes on its overly large property grants. For example, in Cologne one third of its built-up land was owned by the church. And further, in some places every tenth person belonged to the clergy! (Today we might phrase it as “too many chiefs, and not enough Indians.” As is usually the case, the chiefs (the church) reaped all the benefits, while the Indians (the common folk) footed the bill.)

Also at that time there was a ground swell in religious piety in Germany which it must be said included some superstition and mysticism. It was a people who believed not only in witches, but also that real tears or blood flowed from some of the many statues of Christ, Mary and the saints. They loved the mystery of the Latin mass, even though they didn’t understand Latin which was the language of scholars and clerics. They saw the mendicant brothers who had no property serving others, and felt that was what they should do. St. Francis was their particular ideal of what they felt the church should be. They did not understand why the hierarchy of the church lived in wealth and debauchery.

Pope Leo X had said that since God had given them the church to rule, they should enjoy it. And enjoy it they did. This meant having mistresses, children out of wedlock, buying and selling offices within the church, and granting high church positions to the highest secular bidder. Often these Rome created secular “clerics” knew nothing about scripture or theology, did not understand Latin, and they neither knew nor cared anything about shepherding their flock. Everything was about money, greed and political power, and was sanctioned by the church.

There was a rise in the middle class at this time. Craft guilds were blossoming and trade was opening up Germany to the rest of the world. A common sense burgher of the time could see the contradiction between the clergy claim of spiritual authority and the scandalous life the clergy was leading. Then came the misuse by sellers of relics (such as bone fragments of dead saints or pieces of the “true cross”), and indulgences (by which anyone could escape purgatory for a fee). These church scams were believed by many of the simple folk, but those exposed to more of the world through business and trade were finding the church abuses hard to swallow.

Another thing which was not sitting well was the sermons by Scholastic priests. These were the well-educated priests and theologians who preached masterpieces of sermons that went right over the heads of the average person. The Scholastic movement in philosophy was represented by theologians such as St. Thomas Aquinas, who thought everything could be systematically proved by reasoning, and set about writing brilliant works to prove it. Everything revolved around God as the First Cause and center of everything, and the church and priest were the arbiters of one’s eternal destiny. This systemized power of priest as definer of the law allowed the ushering in of excommunication and interdict of “heretics” who were saying things to which the church took exception. Torture and death were the order of the day.

As a reaction to this philosophy, a movement called humanism came about with Erasmus of the Netherlands as its chief proponent. The humanist idea places man in the center of things instead of God. It scoffed at the ignorance of many priests, superstitions of the people, excess and misuse of church ritual and behavior, and what they considered the artificial and empty subtleties of scholasticism. It promoted the idea that man had dignity and a moral consciousness that could unite man in all times and places. Erasmus’ ideas mainly appealed to the aristocracy of the time, but once again it was too high brow for the average citizen of that day. Some of its ideas did trickle down, however, and it became a precursor of the Enlightenment period. As a secular religious philosophy it is alive and well today.

Another thing happening was that Germany, like most countries of that time, was not really a country as we know it today. It was a very loose federation of kingdoms, dukedoms, archbishoprics, etc. with everyone wanting control of his piece of the pie. At the same time a nationalistic feeling was on the rise. There was the Holy Roman Emporer as titular secular (but who was controlled by the church, or controlled the church depending on the time) emporer elected by seven electors. He was also king of Spain, Netherlands and Archduke of Austria. There was a king in France, and Germany was becoming more nationalistic. They began seeing themselves as separate and apart from the countries around them. A Germanic culture with its own Germanic myths and ideas of freedom was arising among the people. Aside from nationalism they also saw that much of the German money and goods given to the church were going over the Alps to Rome. They wanted to keep it in their own homeland.

Lastly, one thing that really helped get the reformation going in Germany  was Gutenberg’s development of the printing press. Up until that time, the educated had a monopoly on what the average person knew because they used Latin in university and church settings. The common folk spoke various forms of German. By Luther’s time translations from Latin into German were being mass produced and disseminated. When Luther put his thoughtful questions on the Wittenberg door they were in Latin and written for the educated clergy to debate amongst themselves. When someone translated them into German, they flew everywhere and ignited a flame of reformation that neither the church nor Luther ever dreamed could happen.

was Gutenberg’s development of the printing press. Up until that time, the educated had a monopoly on what the average person knew because they used Latin in university and church settings. The common folk spoke various forms of German. By Luther’s time translations from Latin into German were being mass produced and disseminated. When Luther put his thoughtful questions on the Wittenberg door they were in Latin and written for the educated clergy to debate amongst themselves. When someone translated them into German, they flew everywhere and ignited a flame of reformation that neither the church nor Luther ever dreamed could happen.